The racist ideas of slave owners are still with us today

The surge in hate crime since the Brexit vote is one legacy of an overlooked period of British history

Monday 26 September 2016 20.32 BST

On Sunday evening, the ITV series Victoria imagined Prince Albert addressing the great anti-slavery convention at Exeter Hall, on the continued existence of the slave trade and slavery. It went so far as to show an encounter between Albert, a freed African-American and American feminists attending the convention.

It was engaging television. But don’t be fooled. People of colour and women were in reality marginalised at this famous 1840 event. And while Albert supported anti-slavery causes, other significant royals, including Victoria’s uncle the Duke of Cumberland, opposed the ending of the slave trade and slavery.

In fact, between 10% and 15% of the 19th-century British elite had connections with slave ownership. Such connections survive today. For example, Princesses Eugenie and Beatrice are descended through their mother, Sarah Ferguson, from Sir Henry Fitzherbert, who in the 18th century owned sugar plantations and more than 1,000 enslaved men, women and children, in Jamaica and Barbados.

Since 2009 I have been working with a team of historians on the Legacies of British Slave Ownership project at University College London. Our initial research was compiled from the records of the compensation paid to slave owners following slavery’s abolition in 1833. This was significant because the compensation paid by British taxpayers contributed in important ways to the making of modern industrial Britain and its empire.

We chose to work on the slave owners – English, Scots, Irish and Welsh, mostly men but also women – as a way of demonstrating the extent to which thousands of white Britons were directly implicated in the exploitation of enslaved Africans. The project has attracted a great deal of attention, and was made into two Bafta-winning TV documentaries.

The key driver of the slave trade was, of course, the desire to make money. But its longer-term legacy runs well beyond that. For in order to make money the traders had to create a new discourse on “race”; and the impact of those ideas needs to be remembered too.

By studying pamphlets, wills, correspondence and other papers kept by slave owners, we can explore how they understood race and attempted to justify their ownership of other people. This week sees the launch of a major new data set and the start of the next phase of work at the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave Ownership at UCL, supported by the Hutchins Center at Harvard.

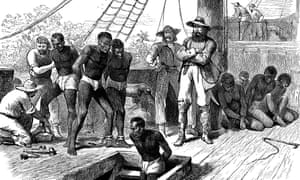

The processes by which Africans became “negroes” who became “slaves”, took place across the African coast, on the slave ships, and on the plantations of the Caribbean. The slave owners’ insistence on skin colour as a marker of identity continues to haunt us. Edward Long’s celebrated History of Jamaica, a key text for pro-slavers and racists who believe in the natural and essential differences between black and white, was first published in 1774 and is still in print today.

Ideas about racial difference that began with slavery were recalibrated across the centuries to encompass other colonised subjects – whether Indian, Aboriginal or east Asian. All were defined as racialised others, inferior to white Britons, and this process was central to imperial rule.

A British history that told this story of exclusion would help us to understand the present. “The great force of history,” wrote the African-American activist and writer James Baldwin, “comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.” The structures and practices that underpin black inequality are not new.

Britain likes to tell a story about itself as a tolerant and inclusive nation, the first to abolish the slave trade and slavery: in essence, of a long slow march from Magna Carta to our contemporary, democratic society. This remains powerful and attempts to challenge or question it are strongly resisted.

History, however, provides us with the means to pursue that questioning. Britons need to grasp a history that takes responsibility for the debt – moral, political and economic – owed to others, to give us a much stronger understanding of the benefits that we at the imperial centre have reaped. One such example is thecurrent campaign by Caribbean nations for reparation, which demands an exploration of the continuities between Atlantic slavery and the present day.

My work as a historian has convinced me that ways of thinking about race are the most destructive legacy of Britain’s imperial past. In the wake of the Brexit vote we have witnessed a deeply disturbing increase in the number of hate crimescommitted against Poles, Muslims and racial minorities. Globalisation, with all the losses it has brought for so many, has clearly acted as a trigger for this upsurge of rage and resentment, the wish to “take back control” and “secure our borders”.

The legacy of slavery is the dehumanisation of others and assumptions of white superiority, as well as terrible disparities of wealth and power. These could not be starker than they are today.